Editor’s note: This story first appeared in the Glenwood Springs Post Independent on Feb. 5, 2017. It is part of a series celebrating Colorado Mountain College’s 50th anniversary this year.

It was hard work to bring together five rural mountain counties to approve their own local property-tax-supported college, but a 2:1 vote in November 1965 set the wheels in motion.

And then the real work began.

Governing Committee member Harold Koonce proposed that the new school be called “Colorado Mountain College,” a name that was adopted unanimously. Early in 1966, the Governing Committee hired the first president, Dr. Joe Davenport.

In April 1967 construction began on the West Campus at Spring Valley, near Glenwood Springs, and one month later at the East Campus, just outside of Leadville. Modular buildings, manufactured in Denver, rolled down the streets of Glenwood and Leadville en route to campus. By September, the scheduled start of classes, carpenters were still feverishly at work.

Right before midnight on Oct. 1, trucks arrived in Leadville with classroom equipment, and faculty and staff were called together to unload and assemble it overnight.

On Oct. 2, 1967, the first classes were held at both campuses.

Loss of first president

To shorten his commute between the West Campus and the East Campus, President Davenport often flew himself. He had only been at the college for one month when he was tragically killed while trying to land his single-engine plane at Glenwood Springs.

After the sudden death of its first president, the stunned and grieving college had to pick up the pieces. Students were enrolled, and the task before the faculty and staff was clear. An interim president, Dr. Ted Pohrte, was hired, and the fledgling college carried on.

In September 1968, the college’s second president, Dr. Elbie Gann, moved with his family to Glenwood Springs, following stints as executive secretary of the Colorado Education Association and superintendent of schools in Aspen. He stayed at Colorado Mountain College for nearly a decade.

“Elbie Gann was a seminal force in collegiate education in Colorado in those days,” said Robin Sutherland, who graduated from Colorado Mountain College in 1972 and is now the pianist with the San Francisco Symphony. “He was the principal author of how to establish a college.”

Demand shapes growth of the college

As the other communities that had voted for the college watched East and West campuses taking shape, they wanted classes, too.

In 1968, the first continuing education courses were offered in Eagle County, and in Aspen, where the staff shared the night sergeant’s desk at the Aspen Police Department. CMC offered summer art classes at the old Anderson Ranch in Snowmass Village. An off-campus office was opened in the basement of Aspen’s Wheeler Opera House. Continuing education was catching on.

But meanwhile, enrollments at the two main campuses were lagging. To publicize the college, President Gann skied with several students from the east side of the Continental Divide to the west. They arrived in a late spring blizzard, surrounded by television crews and reporters.

Ranchers, hippies, miners

Alumnus Sutherland said that in the early days, “there were no so-called permanent buildings. Everything was waiting for something else. Classrooms were double-wide trailers. Dorms were round from a birds’ eye view, dorm rooms were cut into pie shapes.”

Already an accomplished pianist, Sutherland had come to the valley “with two garage-band mates” to attend the college-preparatory Colorado Rocky Mountain School in 1968. In part thanks to connections he’d made in Aspen, he was accepted into The Juilliard School in New York, with intentions to study with the renowned Rosina Lhevinne. But she was elderly, and when it became clear she wouldn’t be able to continue teaching, he decided to leave the prestigious school. Directionless, he returned to the “absolute familiarity” of the Roaring Fork Valley, and place that he had found transformational.

“So during that time I was sitting and thinking, CMC came along and it was natural,” he said. Not only did he become a student and vice president of the student government, he was tapped to start an artist-in-residence program. He gave concerts on campus, taught other students and became “thick as thieves” with legendary valley musician Betsy Schenck. They both taught at CMC, and together gave concerts on Missouri Heights.

The college continued the blending of ranching, the arts and academics that had begun with the start of Colorado Rocky Mountain School a decade and a half earlier. CMC drew artists like Sutherland and Schenck, intellectuals like the first Governing Board Chairman Harold Koonce (a Harvard MBA), blending with the miners from Leadville’s Climax Molybdenum mine and resident ranchers like the families at Spring Valley.

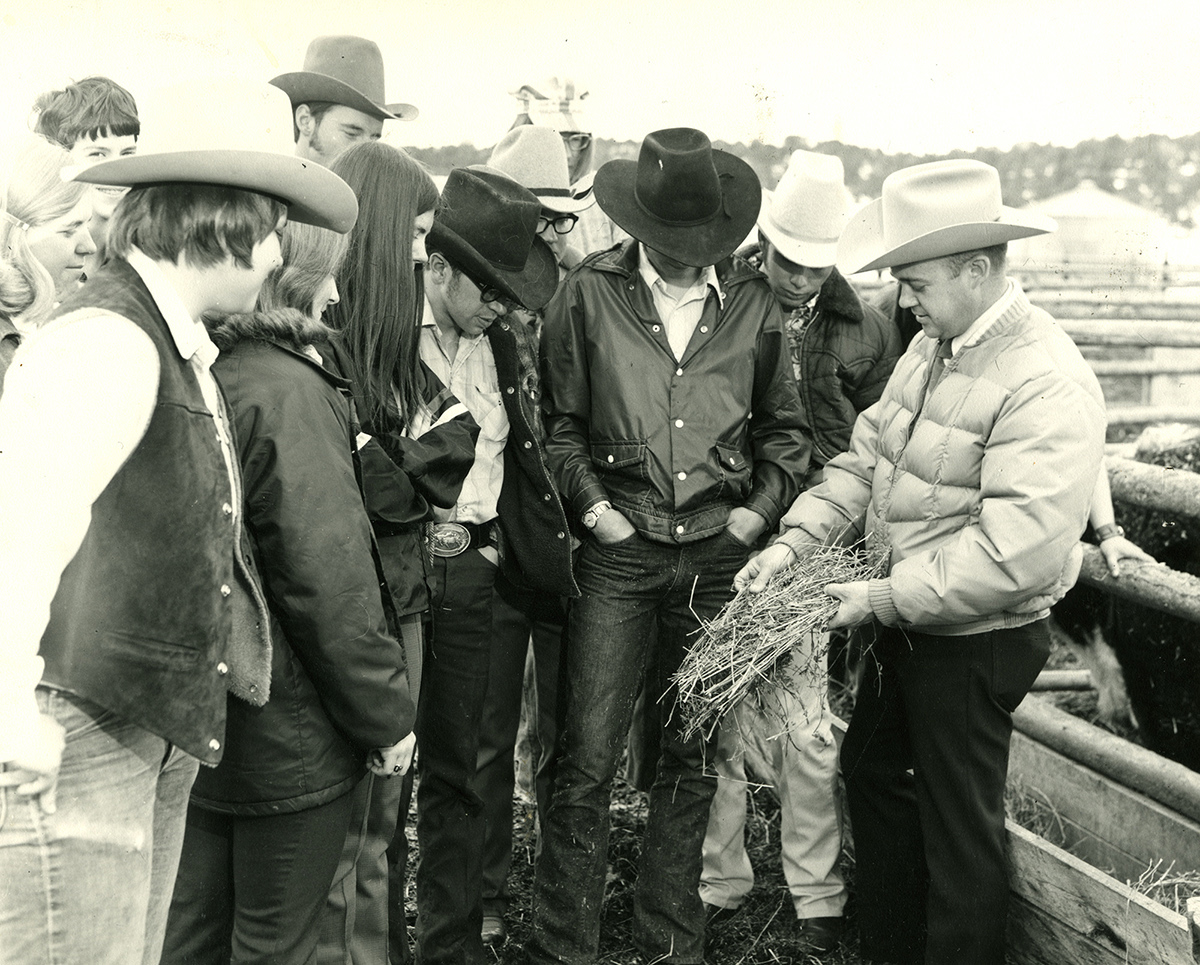

With roots deep in ranching, it was natural that the West Campus should start a farm ranch management program. Shortly after the program’s first class graduated in 1970, Bill Wright was hired to run that program, which he did for 11 years. He credits the strength of the program in large part to support from his advisory council, which included in part Tom Turnbull, Dr. Carter Jackson, Ray Cogburn, Jim Nieslanik and John Benton.

“The farm ranch program did well, but it would not have been what it was if it had not been for the Quigleys and Nieslaniks and the neighboring ranchers who supported it, and I give them an awful lot of credit and thanks,” says Wright.